Abstract

Adaptogens are synthetic compounds (bromantane, levamisole, aphobazole, bemethyl, etc.) or plant extracts that have the ability to enhance the body’s stability against physical loads without increasing oxygen consumption. Extracts from Panax ginseng, Eleutherococcus senticosus, Rhaponticum carthamoides, Rhodiola rosea, and Schisandra chinensis are considered to be naturally occurring adaptogens and, in particular, plant adaptogens. The aim of this study is to evaluate the use of plant adaptogens in the past and now, as well as to outline the prospects of their future applications. The use of natural adaptogens by humans has a rich history—they are used in recovery from illness, physical weakness, memory impairment, and other conditions. About 50 years ago, plant adaptogens were first used in professional sports due to their high potential to increase the body’s resistance to stress and to improve physical endurance. Although now many people take plant adaptogens, the clinical trials on human are limited. The data from the meta-analysis showed that plant adaptogens could provide a number of benefits in the treatment of chronic fatigue, cognitive impairment, and immune protection. In the future, there is great potential to register medicinal products that contain plant adaptogens for therapeutic purposes.

1. Introduction

Adaptogens are pharmacologically active compounds or plant extracts from different plant classes (for example: Araliaceae—Panax ginseng, Eleutherococcus senticosus, Asteraceae—Rhaponticum carthamoides, Crassulaceae—Rhodiola rosea, and Schisandraceae—Schisandra chinensis) [1,2,3]. They have the ability to enhance the body’s stability against physical loads without increasing oxygen consumption. The intake of adaptogens is associated not only with the body’s better ability to adapt to stress and maintain/normalize metabolic functions, but also with better mental and physical performance [1,2,3].

There are two main classes of adaptogens. The first class includes plant adaptogens, while the other includes synthetic adaptogens, which are also called actoprotectors.

Although plant adaptogens have been used by people since ancient times, the term “adaptogen” is relatively young—it was introduced in 1947 by the Soviet scientist Lazarev [1,4]. It defines adaptogens as substances that cause non-specific resistance of the living organisms [1,2,4]. Adaptogens have a positive effect on humans and animals. The use of plant adaptogens has a rich history. They have been used by man for hundreds of years in different parts of the world, while data on the use of the first synthetic adaptogen, bemethyl, date back to the 1970s. Bemethyl was introduced in the 1970s by Professor Vladimir Vinogradov. Since then, numerous synthetic adaptogens have been developed: bromantane, levamisole, aphobazole, chlodantane, trekrezan. Their intake is associated not only with increased physical and mental resistance, but also with vasodilation and decreased blood sugar and lactate [3]. They are widely used in sports medicine, but since 2009, WADA has included bromantane in the prohibited list and since 2018, bemethyl has also been included in the monitoring program of WADA [5,6].

In 1980, the scientists Breckham and Dardimov found that adaptogens increase the body’s resistance not only to physical but also to chemically and biologically harmful agents [1,2,7], which further expands the potential of their use.

Breckham and Dardimov systematized the plants with adaptogenic properties. These are: Panax ginseng, Eleutherococcus senticosus, Rhaponticum carthamoides, Rhodiola rosea, and Schisandra chinensis [7].

Although plant adaptogens have been used for centuries, their effects continue to be studied to this day. They also have promising potential for wider applications in the future.

The biological effects of plant adaptogens are related to the complex of biologically active compounds they contain. Plant adaptogens have very rich phytochemical composition. Some of the most important phytochemicals with adaptogenic properties are: triterpenoid saponins (in Panax ginseng—ginsenosides; in Eleutherococcus senticosus—eleutherosides); phytosterols and ecdysone (in Rhaponticum carthamoides); lignans (in Schisandra chinensis); alkaloids; flavonoids, vitamins, etc. [4,8,9].

The mechanism of action of the plant adaptogens is complex and is not fully understood. Recent studies report that the intake of plant adaptogens like extracts of Eleutherococcus senticosus root, Schisandra chinensis root, Rhodiola rosea root is associated with affecting the hypothalamic—pituitary—adrenal axis [10] and some stress mediators [11]. Moreover, the intake of such extracts affects nitric oxide levels, lactate levels, blood glucose levels, cortisol levels, plasma lipid profile, hepatic enzymes, etc. [8,11,12,13,14].

Current and potential uses of these medicinal plants are associated with mental diseases and behavioural disorders, cognitive function and stress-induced diseases (anxiety, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes) [4,9,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The intake of plant adaptogens is not associated with serious side effects [20,21].

The aim of our study is to evaluate the data about the use of adaptogens in the past and the future perspectives of their use.

2. Materials and Methods

The first step of the screening process included identifying eligible studies. An expanded search for articles without language restrictions was conducted on the following databases: Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science. In the search process, the following search key words were used: “adaptogens”, “actoprotectors”, “plant adaptogens”, “Panax ginseng”, “Eleutherococcus senticosus”, “Schisandra chinensis”, “Rhodiola rosea”, “Rhaponticum carthamoides”, “Leuzea carthamoides”, “ginseng adaptogen properties study”, “Eleutherococcus senticosus adaptogen properties study”, “randomized controlled study Eleutherococcus senticosus”, “Leuzea carthamoides adaptogen properties study”, “Rhaponticum carthamoides adaptogen properties study”, "ecdysterone adaptogen properties study”, “20-hydroxyecdisone adaptogen study”, “ecdysterone from Leuzea adaptogen studies”, “Leuzea carthamoides adaptogen properties in rats”, “performance gain Rhaponticum carthamoides”, “Rhodiola rosea in sport”, “Rhodiola rosea adaptogen properties study”, “Schisandra chinensis in sport”, “Schisandra chinensis randomized study”, “Schisandra chinensis adaptogen properties study”, and “Schisandra chinensis mice study”.

Further records concerned the history of plant adaptogens, botanical and phytochemical characteristics, and application of adaptogens.

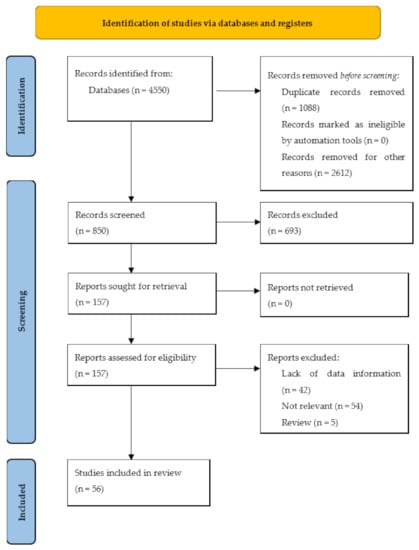

In the second step, we followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) presented in Figure 1 [22], guide for a systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only.

In the third step, the relevant studies were chosen based on exclusion and inclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were: (i) articles written in a language other than English or Russian; (ii) webinars or blogs; (iii) articles with irrelevant topics, and (iv) lack of data information. Inclusion criteria were: (i) human studies; (ii) animal studies, and (iii) studies investigating the impacts of adaptogens.

During the fourth step, the selected full articles were read and identified.

In total, 56 studies were selected and included in the present review.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Panax Ginseng

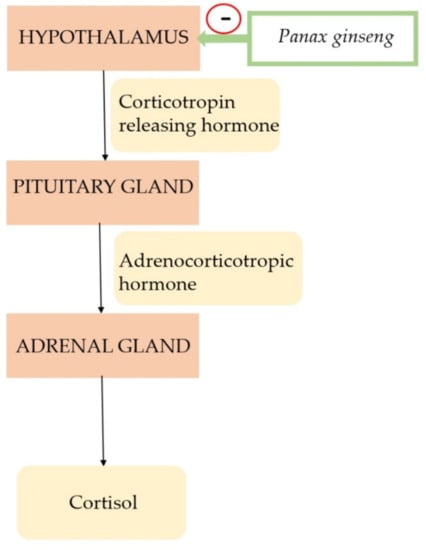

The first evidence of the use of Panax ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Mey.) dates back more than 2000 years [23]. In the past, the stems, leaves, and mainly the roots of ginseng were used. Extracts were prepared and used to maintain homeostasis in the human body, treat fatigue and weakness, increase immune protection, and treat hypertension, diabetes type 2, and erectile dysfunction [2,23,24,25,26]. In Chinese traditional medicine, ginseng extracts have also been used as nootropic agents and as a tonic [24,25,26]. The exact mechanism of adaptogenic action of Panax ginseng is unknown, but it is supposed that it affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in Figure 2 and the antioxidant effect [24,27,28,29].

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of Panax ginseng.

Panax ginseng is an example of a medicinal plant, widely used in ancient times, but also with great application today. It is also one of the plants defined as a natural adaptogen.

Panax ginseng has a rich botanical phytochemical composition. Today, more than 200 substances isolated from Korean ginseng are known, ginsenosides predominantly: Ra1, Ra2, Ra3, malonyl-G-Rb1, malonyl-G-Rb2, malonyl-G-Rc, malonyl-GRd, Rs1, Rs2, Rs3, Rg3, Rg5, Rh2, K-R2, Rf, Rf2, 20(R)-G-Rg2, Rg6, 20(R)-G-Rh1, 20(E)-G-F4, Rh4, K-R1, and poly-acetyleneginsenoside-Ro [30].

It is considered that the adaptogenic properties of Panax ginseng extract are due to the ginsenosides [27].

Nowadays, numerous products containing ginseng extracts are available. Most of these products are sold as food supplements but there are also many over-the-counter medicines. Ginseng radix is included in European Pharmacopeia and in the US Pharmacopeia. The principal root has a cylindrical form, sometimes branched, up to about 20 cm long and 2.5 cm in diameter. Its surface is pale yellow/cream in white ginseng, while it is brownish-red in red ginseng. The rootlets, which are many in the lower part of white ginseng, are usually absent in red ginseng. Reduced to a powder, it is light yellow. Ginseng dry extract is produced from the root by a suitable procedure using a hydroalcoholic solvent equivalent in strength to ethanol. The main compounds that can be detected in the extract are: ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re, ginsenoside Rf, ginsenoside Rb1, ginsenoside Rc, ginsenoside Rd, ginsenoside Rb2 [31].

Although the extract has been used for more than two millenniums, there are a limited number of clinical studies that have investigated the benefits or the side effects of its use. More double-blind randomized studies are needed to be performed.

In Table 1, we have summarized the main benefits of the Panax ginseng extract intake.

Table 1.

Panax ginseng studies.

The data suggest that an intake of Panax ginseng extracts is associated with ergogenic effects and enhanced muscle strength. The inclusion of Panax ginseng in the diet of athletes would help increase the body’s physical resilience and help the body recover between workouts.

Intake of Panax ginseng extract is associated also with improved plasma lipid profile and blood glucose level. Extracts of Panax ginseng might be included in the diet of patients with cardiovascular diseases, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Extracts from the plant not only increase cognitive function and memory functions, but also improve sleep and fatigue.

We did not find multicenter randomized double-blind studies including the intake of Panax ginseng. For better exploration of the benefits and future applications of the Panax ginseng extract, multicenter randomized double-blind studies should be performed. The plant has a great potential to be included in medicines for treatment of different conditions.

The intake of Panax ginseng extract is not associated with serious side effects [21,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The safety of the extract is another benefit to be considered.

3.2. Eleutherococcus Senticosus

Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus ((Rupr. and Maxim.) Maxim.) was first described by Porfiry Kirilov in the 19th century [42]. Its adaptogenic effects were widely studied in Russia between 1960 and 1970 [43]. The first data on the use of plant extracts in athletes were reported from Russia. Today, plant extracts are used not only by athletes around the world, but also by many other consumers who are not actively involved in sports.

The phytochemical composition consists of phenylpropanoid—syringin; lignans—sesamin; saponins—daucosterol; coumarins, terpenoids, flavonoids, organic acids, and vitamins [44,45]. Extracts of Eleutherococcus senticosus root are obtained, stimulating the immune system, influencing adaptation against external factors, improving mental and physical conditions and memory functions, and have a hypoglycaemic effect and are anti-inflammatory [13,45,46]. Eleutherococcus senticosus is thought to exert its adaptogenic effects by influencing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [44].

Most of the extracts of Eleutherococcus senticosus are prepared by the roots. The rhizome of Eleutherococcus senticosus is described in European pharmacopeia. The rhizome has a diameter of 1.5 to 4 cm and an irregular cylindrical shape. The surface is longitudinally wrinkled with grayish-brown to blackish-brown colour [47].

Although Eleutherococcus senticosus were described a few hundred years ago, research into its use continues. In Table 2, we summarized results of studies with Eleutherococcus senticosus.

Table 2.

Eleutherococcus senticosus studies.

The data suggest that the intake of Eleutherococcus senticosus supports the physical activity, weight reduction, mental health, and fatigue. Extracts of the plant can be used only for fatigue, but also in the case of disturbed sleep.

The intake of Eleutherococcus senticosus extract may help to increase the cognitive function. Siberian ginseng extract could be included in the diet of patients with hyperlipidemia because it has a beneficial effect on the lipid profile. There is a potential for development of medicinal products containing Eleutherococcus senticosus extract to be taken by patients with various pathologies such as: obesity, overweight, hyperlipidemia, etc. New nootropic drugs containing a standardized plant extract could also be registered.

We did not find multicenter randomized double-blind studies that included the intake of Siberian ginseng. For better exploration of the benefits and future applications of the Eleuterococcus senticosus extract, multicenter randomized double-blind studies should be performed. The plant has a great potential to be included in medicines for treatment of different conditions; moreover, the intake of Eleuterococcus senticosus extract is not associated with serious side effects [46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

3.3. Rhaponticum Carthmoides

Rhaponticum carthamoides (Rhaponticum carthamoides IIjin.) is a perennial herb which has been used for centuries in Russia, China, and Mongolia [14]. The plant is also known as Leuzea. Extracts of the plant have been used to treat weakness [14,56], lung diseases, kidney diseases, fever, and angina [57].

In 1969, Brekhman and Dardymov classified this plant as an adaptogen [14]. The use of products containing Rhaponticum carthamoides root extract has increased in recent decades. The extract has many beneficial effects on humans like: enhanced physical endurance and performance, anabolic effect, hypocholesterolemic effects, neuroprotective effect, antidiabetic properties, anti-oxidative, and increased immunity [14,57]. The mechanism by which ecdysteroids act is binding with signal transduction pathways, rather than with steroid and estrogen receptors [58].

In the 1970s, the extracts from Leuzea showed beneficial effects in athletes and their use became a routine practice in the training of many athletes. The intake of Leuzea extract increases the body’s adaptation to various factors, which can be defined as stress for the body [14,57] and at the same time has a good level of safety.

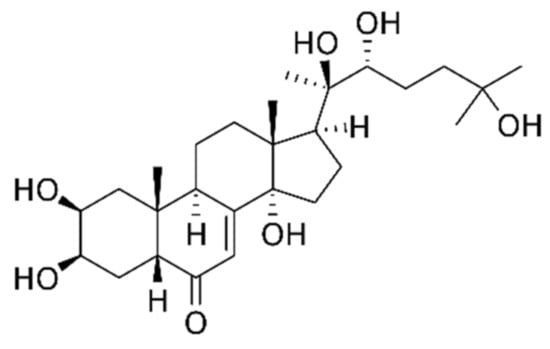

The phytochemical composition of Rhaponticum carthamoides is rich of ecdysteroids and phenols. The main ecdysteroid is 20-hydroxyecdysone in Figure 3 [14]. The adaptogenic properties of the extract are related mainly to its presence [14]. Other components of the phytochemical composition are phenols and essential oil [14].

Figure 3.

20-hydroxyecdysone structure.

20-hydroxyecdysone has a typical steroidal structure. A recent study, funded by WADA and conducted in 2019, reported 20-hydroxyecdisone as a non-conventional anabolic agent, which can significantly increase the muscle mass. A significant dose-responsive anabolic effect of 20-hydroxyecdysone was reported [59].

In 2020, 20-hydroxyecdysone was included in the WADA monitoring program and it is very likely that the substance will be included in the prohibited list in the next few years [60]. In the past few years, other adaptogens were included in WADA’s prohibited list and monitoring program, because these compounds were considered to improve the performance of the athletes. Bromantane is included in the prohibited list as a non-specified stimulant. Since 2018, bemethyl is monitored by WADA, but it is still not included on the prohibited list [5,6]. The main difference between 20-hydroxyecdysone and these two compounds is that 20-hydroxyecdysone is a natural compound while the other two are synthetic adaptogens. The main reason 20-hydroxyecdysone is monitored by WADA is that the intake of this compound improves the performance of athletes. Nowadays, food supplements containing Leuzea (which contain 20-hydroxyecdysone) are often included in the supplementation of professional athletes.

Table 3 presents studies related to the use and effects of Rhaponticum carthamoides.

Table 3.

Rhaponticum carthamoides studies.

We expanded our search with animal studies; found results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Rhaponticum carthamoides animal studies.

The data suggest that intake of Rhaponticum carthamoides extracts is associated with anabolic effects—increased body mass weight and enhanced muscle strength. Other important benefits are improved mental endurance and improved plasma lipid profiles. Improvement of cardiac and cognitive functions has also been reported.

Because of improvement in cardiac functions, the Rhaponticum carthamoides extract might be especially useful for patients with cardiovascular diseases.

Despite the benefits of the extract use, the studies on humans are limited in number and not sufficient for a more complete and comprehensive assessment.

The anabolic effects were also reported in animal studies. The data from animal studies suggests that application of Rhaponticum carthamoides is also associated with a neuroprotective effect.

The intake of Rhaponticum carthamoides is not associated with serious side effects [19,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

The data obtained from human and animal studies about synergetic anabolic effect of Rhaponticum carthamoides and Rhodiola rosea are contradictory. Further studies are needed to confirm the synergetic effect of these adaptogenic plants.

For better exploration of the benefits and future applications of the Rhaponticum carthamoides extract, more in vivo studies and multicenter randomized double-blind studies should be performed.

3.4. Rhodiola rosea

In traditional medicine, its (Rhodiola rosea L.) applications are described as an adaptive agent that increases physical endurance, affects fatigue, depression, and disorders of the nervous system. It has been used in the past in Asia to treat flu and colds, and there is reported use in tuberculosis. In the Scandinavian part of Europe, plant extracts have been used to increase physical endurance [73].

Six groups of compounds predominate in the phytochemical composition of the plant: phenylpropanoids, phenylethanol derivatives, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and mono- and triterpene [74].

The main phenylethanol derivatives are salidroside (rhodioloside), para-tyrosol, and phenylpropanoid-rosavin. These are also responsible for the adaptogenic and ergogenic effects of Rhodiola rosea [8,73,75].

The adaptogenic effect of Rhodiola rosea is associated with activation of the cerebral cortex by increasing norepinephrine and serotonin levels. In addition, it affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, reducing the levels of corticotropin-releasing hormones, corticotropin, cortisol, and epinephrine [29,73,76].

Studies of Rhodiola rosea began with Dioscorides and continues nowadays. In Table 5, we summarized beneficial effects of Rhodiola rosea based on studies.

Table 5.

Rhodiola rosea studies.

The data suggest that the intake of the extract of Rhodiola rosea is associated with antioxidant and adaptogen properties. Rhodiola rosea extract might be used not only for overcoming the fatigue but might be included in the diet of people with heart diseases, because of the beneficial effect on heart rate and muscle contractions. The use of plant extracts is recommended for sleep disorders and anxiety. The hepatoprotective effect of the plant determines the use of its extract in liver diseases. Improving physical strength during exercise and recovery after training are the reasons why Rhodiola rosea extracts are also taken by athletes as a supplement to their diet.

The intake of Rhodiola rosea is not associated with serious side effects [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86].

For better exploration of the benefits and future applications of the Rhodiola rosea extract, more multicenter randomized double-blind studies should be performed. The plant has a great potential to be included in medicines for treatment of different conditions.

3.5. Schisandra chinensis

Schisandra chinensis (Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Bail) is first described in the book Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, around 200 AD, as a remedy for cough and asthma [87]. In the past, Schisandra chinensis fruits and seeds were used to improve night vision, reduce hunger, thirst, and exhaustion. In 1960 in Russia, the adaptogenic properties of the plant were proven [88]. The fruits of Schisandra chinensis are used today [87,88,89,90].

According European Pharmacopoeia, Schisandra berry is more or less spherical, up to 8 mm in diameter. It could be red/reddish-brown/blackish, it could be covered in a whitish frost. It has a strongly shriveled pericarp. The seeds are only 1 or 2, yellowish-brown and lustrous. The seed-coat is thin [91].

For production of the extract, the fruit should be reduced to a powder. The colour of powder should be reddish-brown.

The Schisandra fruit has a complex phytochemical composition in which the lignans are the major characteristic constituents. Five classes of different lignans are found in the fruits of Schisandra: dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans (type A), spirobenzofuranoid dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans (type B), 4-aryltetralin lignans (type C), 2,3-dimethyl-1,4-diarylbutane lignans (type D), and 2,5-diaryltetrahydrofuran lignans (type E) [88].

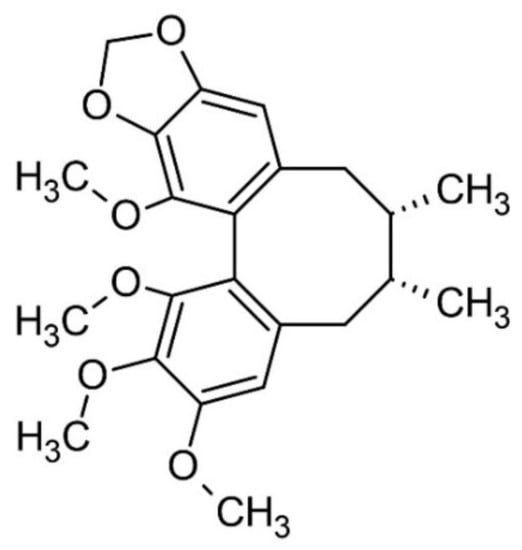

The adaptogenic properties of Schisandra chinensis are due to the lignin complex, mainly dibenzocycloocstadiene lignans, the main schisandrin [92,93]. Schizandrin was isolated and identified for the first time by N.K. Kochetkov in 1961 [88,92,93].

One of methods for identification of the plant, described in the European Pharmacopeia, involves a TLC technique with identification of γ-Schisandrin in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Structure of γ-Schisandrin.

Several studies reported that some lignans (gomisin A, gomisin G, schizandrin, and schisanhenol) possess antitumor bioactivities [94,95,96,97,98].

The Schisandra fruit, particularly the seeds, contains many volatile compounds as well: α-ylangene, α-cedrene, β-chamigrene, and β-himachalene [99,100].

From Schisandra chinensis fruit are also isolated polysaccharides, glycosides (dihydrophaseic acid-3-O--d-glucopyranoside, benzyl alcohol-O--d-glucopyranosyl (1→6)--d-glucopyranoside and benzyl alcohol-O--d-glucopyranosyl (1→2)--d-glucopyranoside), organic acids (vitamin C, malic acid, citric acid, and tartaric acid), and vitamin E. [12,87,101,102]. In small quantities, the fruit of Schisandra chinensis contained flavonoids such as rutine [103]. Preschsanartanin, schintrilactones A–B, schindilactones A–C, and wuweizidilactones A–F are the new isolated triterpenoids from Schisandra chinensis fruit [88].

All of phytochemicals determined beneficial effects such as: cytotoxic, antioxidant, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, increased physical strength, stress-protective, anti-inflammatory [12,88,104]. The adaptogenic effect of Schisandra chinensis is associated with the antioxidant effect and the influence on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by lowering the level of corticotropin-releasing hormone [29,76].

Research on the effects of Schisandra chinensis continues.

In Table 6, we present summarized data about beneficial effects of Schisandra chinensis.

Table 6.

Schisandra chinensis studies.

Discovered trials are insufficient to summarize the use of Schisandra chinensis. We expanded our search with animal studies, the results found are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Schisandra chinensis animal studies.

The data from animal and human studies suggest that the application of extract of Schisandra chinensis is associated with adaptogenic, antioxidant properties, tonic, and stress-protective effect.

The intake of plant extract can improve memory and concentration. The plant extract has serious potential to be included in medicinal products for use in the treatment of patients with hypercholesterolemia or patients with cardiovascular disease. Of course, the application of the extract would have a number of benefits in healthy patients due to its pronounced antioxidant properties.

The positive effect of the plant on blood sugar and liver enzymes suggests the inclusion of Rhodiola rosea extracts in the treatment of patients with diabetes and liver disease. In recent decades, Schisandra chinensis extract has been taken by athletes to increase physical activity and the body’s adaptation to stress.

The studies on humans are limited in number, so a full assessment of the effects is difficult to make.

The intake of Schisandra chinensis is not associated with serious side effects [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116].

For a better exploration of the benefits and future applications of the Schisandra chinensis extract, more in vivo studies and multicenter randomized double-blind studies should be performed.

4. Conclusions

The natural adaptogens have the ability to increase the body’s resistance to stress changes caused by different types of stressors. Unlike the synthetic adaptogens, the natural are extracts with an extremely rich phytochemical composition. Their adaptogenic properties are not due to one molecule, but to the combination of different substances. The use of natural adaptogens by humans has a rich history—they have been used in recovery from illness, physical weakness, impaired mental function, and other conditions. For about 50 years, plant adaptogens have been used by professional athletes due to their high potential to increase the body’s resilience and improve physical endurance. Nowadays, some of the most used plant adaptogens are Panax ginseng, Eleutherococcus senticosus, and Rhaponticum carthamoides. Since 2020, ecdysterone, which is rich in Leuzea extract, has been included in WADA’s monitoring program, with prospects for inclusion in the prohibited list. Studies examining the benefits of using extracts of Rhodiola rosea, Eleutherococcus senticosus, Panax ginseng, Schisandra chinensis and Rhaponticum carthamoides are a limited in number. However, there are potentials for the inclusion of the extracts of these plants in medicinal products aimed at treating chronic fatigue, cognitive impairment, as well as boosting immune defenses. Double-blind randomized multicenter studies would be extremely valuable in evaluating the use of the extracts in patients with cardiovascular disease, in patients with compromised immunity, and in patients with chronic fatigue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.T., K.I. and S.I.; data curation, V.T. and S.I.; writing—original draft preparation, V.T., K.I., C.D., V.N., D.K.-B. and S.I.; writing—review and editing, K.I., C.D., V.N., D.K.-B. and S.I.; visualization, V.T., K.I., V.N., D.K.-B. and S.I.; supervision, K.I. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wagner, H.; Nörr, H.; Winterhoff, H. Plant adaptogens. Phytomedicine 1994, 1, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A.; Wikman, G.; Wagner, H. Plant adaptogens III. Earlier and more recent aspects and concepts on their mode of action. Phytomedicine 1999, 6, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliynyk, S.; Oh, S.-K. The pharmacology of Actoprotectors: Practical application for improvement of mental and physical performance. Biomol. Ther. 2012, 20, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Panossian, A.G.; Efferth, T.; Shikov, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Kuchta, K.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Banerjee, S.; Heinrich, M.; Wu, W.; Guo, D.; et al. Evolution of the adaptogenic concept from traditional use to medical systems: Pharmacology of stress and aging related diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 41, 630–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Anti-Doping Agency—WADA. Executive Committee Approved the List of Prohibited Substances and Methods for 2009. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/media/news/2008-09/wada-executive-committee-approves-2009-prohibited-list-new-delhi-laboratory-0 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- The World Anti-Doping Agency—WADA. Prohibited List. 2018. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/prohibited_list_2018_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Brekhman, A.I.; Dardymov, I.V. New substances of plant origin which increase nonspecific resistance. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. 1969, 9, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.S. Rhodiola rosea: A possible plant adaptogen. Altern. Med. Rev. 2001, 6, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.; Arif, M.; Jawaid, T. Adaptogenic medicinal plants utilized for strengthening the power of resistance during chemotherapy—A review. Orient. Pharm. Exp. Med. 2017, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A.; Wikman, G.; Kaur, P.; Asea, A. Adaptogens exert a stress-protective effect by modulation of expression of molecular chaperones. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, V.S.; Shivakumar, H. A current status of adaptogens: Natural remedy to stress. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2012, 2, S480–S490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Feng, J. A review of polysaccharides from Schisandra chinensis and Schisandra sphenanthera: Properties, functions and applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 184, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikino, H.; Takahashi, M.; Otake, K.; Konno, C. Isolation and Hypoglycemic Activity of Eleutherans A, B, C, D, E, F, and G: Glycans of Eleutherococcus senticosus Roots. J. Nat. Prod. 1986, 49, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoska, L.; Janovska, D. Chemistry and pharmacology of Rhaponticum carthamoides: A review. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. Understanding adaptogenic activity: Specificity of the pharmacological action of adaptogens and other phytochemicals. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1401, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.R.; Carlini, E. Brazilian plants as possible adaptogens: An ethnopharmacological survey of books edited in Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 109, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, T.O. The effects of adaptogens on the physical and psychological symptoms of chronic stress. DISCOV. Ga. State Honor. Coll. Undergrad. Res. J. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, A.M. Effects of adaptogen supplementation on sport performance. A recent review of published studies. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2013, 8, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krasutsky, A.G.; Cheremisinov, V.N. The use of Levzey’s extract to increase the efficiency of the training process in fitness clubs students. In Proceedings of the Actual Problems of Biochemistry and Bioenergy of Sport of the XXI Century, Moscow, Russia, 10–26 April 2017; pp. 382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanyan, G.; Amroyan, E.; Gabrielyan, E.; Nylander, M.; Wikman, G.; Panossian, A. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised study of single dose effects of ADAPT-232 on cognitive functions. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, J.L.; Scholey, A.; Kennedy, D. Panax ginseng (G115) improves aspects of working memory performance and subjective ratings of calmness in healthy young adults. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2010, 25, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeg, I.-H.; So, S.-H. The world ginseng market and the ginseng (Korea). J. Ginseng Res. 2013, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiefer, D.S.; Pantuso, T. Panax ginseng. Am. Fam. Physician 2003, 68, 1539–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Rauf, A. Adaptogenic herb ginseng (Panax) as medical food: Status quo and future prospects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 85, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shergis, J.; Zhang, A.L.; Zhou, W.; Xue, C.C. Panax ginseng in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review. Phytother. Res. 2012, 27, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocerino, E.; Amato, M.; Izzo, A. The aphrodisiac and adaptogenic properties of ginseng. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahady, G.B.; Gyllenhaal, C.; Fong, H.H.; Farnsworth, N.R. Ginsengs: A review of safety and efficacy. Nutr. Clin. Care 2000, 3, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L. Review of adaptogenic mechanisms: Eleuthrococcus senticosus, panax ginseng, rhodiola rosea, schisandra chinensis and withania somnifera. Aust. J. Med. Herbal. 2007, 19, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Ginsenosides: Chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2008, 55, 1–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care. Ginseng radix. In European Pharmacopoeia, Monograph 07/2019:1523; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care: Strasburg, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, K.S. Effects of panax ginseng extract on lipid metabolism in humans. Pharmacol. Res. 2003, 48, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, I.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Effects of acute supplementation of panax ginseng on endurance performance in healthy adult males of Kolkata, India. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Physiol. 2020, 7, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadifar, M.; Sayahi, F.; Abtahi, S.-H.; Shemshaki, H.; Dorooshi, G.-A.; Goodarzi, M.; Akbari, M.; Fereidan-Esfahani, M. Ginseng in the treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot study. Int. J. Neurosci. 2013, 123, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, H.-J.; Said, J.M.; Wirth, J.C. Failure of chronic ginseng supplementation to affect work performance and energy metabolism in healthy adult females. Nutr. Res. 1996, 16, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzo, F.F.; Fonseca, F.L.; Souza, G.H.B.; Maistro, E.L.; Rodrigues, M.; Carvalho, J.C. Double-blind clinical study of a multivitamin and polymineral complex associated with panax ginseng extract (Gerovital®). Open Complement. Med. J. 2010, 2, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ziemba, A.W. The effect of ginseng supplementation on psychomotor performance, indices of physical capacity and plasma concentration of some hormones in young well fit men. In Proceedings of the Ginseng Society Conference, Seoul, Korea, 1 October 2002; pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zarabi, L.; Arazi, H.; Izadi, M. The effects of panax ginseng supplementation on growth hormone, cortisol and lactate response to high-intensity resistance exercise. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 10, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.A.; Kang, S.G.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, K.Y.; Kim, L. Effect of Korean red ginseng on sleep: A randomized, placebo-controlled Trial. Sleep Med. Psychophysiol. 2010, 17, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-G.; Cho, J.-H.; Yoo, S.-R.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, J.-M.; Lee, N.-H.; Ahn, Y.-C.; Son, C.-G. Antifatigue Effects of Panax ginseng CA Meyer: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ping, F.W.C.; Keong, C.C.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Effects of acute supplementation of Panax ginseng on endurance running in a hot & humid environment. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 133, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Davydov, M.; Krikorian, A. Eleutherococcus senticosus (Rupr. & Maxim.) maxim. (Araliaceae) as an adaptogen: A closer look. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 72, 345–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakney, T.L. Deconstructing an adaptogen: Eleutherococcus Senticosus. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2008, 22, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Deng, B.; Qiu, Z.; Fu, C. A review of Acanthopanax senticosus (Rupr and Maxim.) harms: From ethnopharmacological use to modern application. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 268, 113586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Takahashi, T.; Miyashita, M.; Matsuzaka, A.; Muramatsu, S.; Kuboyama, M.; Kugo, H.; Imai, J. Effect of eleutheroccocus senticosus extract on human physical working capacity. Planta Med. 1986, 52, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care. Eleutherococci radix. In European Pharmacopoeia, Monograph 01/2008:1419; Corrected 7.0; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care: Strasburg, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, E.A.; Redondo, D.R.; Branch, J.D.; Jones, S.; McNabb, G.; Williams, M.H. Effect of Eleutherococcus senticosus on submaximal and maximal exercise performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, J.; Chen, K.W.; Cheng, I.S.; Tsai, P.H.; Lu, Y.J.; Lee, N.Y. The effect of eight weeks of supplementation with Eleutherococcus senticosus on endurance capacity and metabolism in human. Chin. J. Physiol. 2010, 53, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cicero, A.; DeRosa, G.; Brillante, R.; Bernardi, R.; Nascetti, S.; Gaddi, A. effects of siberian ginseng (eleutherococcus senticosus maxim.) on elderly quality of life: A randomized clinical trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2004, 38, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szołomicki, S.; Samochowiec, L.; Wójcicki, J.; Droździk, M. The influence of active components of eleutherococcus senticosus on cellular defence and physical fitness in man. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffler, K.; Wolf, O.; Burkart, M. No Benefit Adding Eleutherococcus senticosus to Stress Management Training in Stress-Related Fatigue/Weakness, Impaired Work or Concentration, A Randomized Controlled Study. Pharmacopsychiatry 2013, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschbach, L.C.; Webster, M.J.; Boyd, J.C.; McArthur, P.D.; Evetovich, T.K. The Effect of Siberian Ginseng (Eleutherococcus Senticosus) on Substrate Utilization and Performance during Prolonged Cycling. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2000, 10, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasutsky, A.G.; Cheremisinov, V.N. Research of the influence of adaptogens on increasing the efficacy of the training process in fitness clubs. In Proceedings of the Current Problems of Biochemistry and Bioenergy Sport of the XXI Centyry, Moscow, Russia, 10–12 April 2018; pp. 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet, A.; Grolleau, A.; Jove, J.; Lassalle, R.; Moore, N. Burnout: Evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of TARGET 1® for professional fatigue syndrome (burnout). J. Int. Med. Res. 2015, 43, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buděšínský, M.; Vokáč, K.; Harmatha, J.; Cvačka, J. Additional minor ecdysteroid components of Leuzea carthamoides. Steroids 2008, 73, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeev, N.P. Leuzea Carthamoides DC: Application prospects as pharmpreparations and biologically active components. In Functional Foods for Chronic Diseases; Martirosyan, D.M., Ed.; Richardson: Texas, TX, USA, 2006; pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bathori, M.; Toth, N.; Hunyadi, A.; Marki, A.; Zador, E. Phytoecdysteroids and anabolic-androgenic steroids—Structure and effects on humans. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isenmann, E.; Ambrosio, G.; Joseph, J.F.; Mazzarino, M.; de la Torre, X.; Zimmer, P.; Kazlauskas, R.; Goebel, C.; Botrè, F.; Diel, P.; et al. Ecdysteroids as non-conventional anabolic agent: Performance enhancement by ecdysterone supplementation in humans. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Anti-Doping Agency—WADA. The 2020 Monitoring Program. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada_2020_english_monitoring_program_pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Vanyuk, A.I. Evaluation of the effectivnness of rehabilitation measures among female volleyball players 18-22 years old in the competitive period of the annual training cycle. Slobozhanskiy Sci. Sports Visnik. 2012, 5, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Timofeev, N.P.; Koksharov, A.V. Study of Leuzea from leaves: Results of 15 years of trials in athletics. New Unconv. Plants Prospect. Use 2016, 12, 502–505. [Google Scholar]

- Wilborn, C.D.; Taylor, L.W.; Campbell, B.I.; Kerksick, C.; Rasmussen, C.J.; Greenwood, M.; Kreider, R.B. Effects of Methoxyisoflavone, ecdysterone, and sulfo-polysaccharide supplementation on training adaptations in resistance-trained males. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2006, 3, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, E.D.; Gerstner, G.R.; Mota, J.A.; Trexler, E.T.; Giuliani, H.K.; Blue, M.N.M.; Hirsch, K.R.; Smith-Ryan, A.E. The acute effects of a multi-ingredient herbal supplement on performance fatigability: A double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled trial. J. Diet. Suppl. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selepcova, L.; Sommer, A.; Vargova, M. Effect of feeding on a diet containing varying amounts of rhaponticum car-thamoides hay meal on selected morphological parameters in rats. Eur. J. Entornol. 2013, 92, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov, M.B.; Aliev, O.I.; Vasil’Ev, A.S.; Andreeva, V.Y.; Krasnov, E.A.; Kalinkina, G.I. Effect of Rhaponticum carthamoides extract on structural and metabolic parameters of erythrocytes in rats with cerebral ischemia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 146, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gao, L.; Shang, L.; Wang, G.; Wei, N.; Chu, T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Ecdysterones from Rhaponticum carthamoides (Willd.) Iljin reduce hippocampal excitotoxic cell loss and upregulate mTOR signaling in rats. Fitoter 2017, 119, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlova-Wuttke, D.; Ehrhardt, C.; Wuttke, W. Metabolic effects of 20-OH-Ecdysone in ovariectomized rats. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 119, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudela, K.; Tenora, J.; Bajer, J.; Mathova, A.; Slama, K. Stimulation of growth and development in Japanase quails after oral administration of ecdysteroid-containing diet. Eur. J. Entomol. 1995, 92, 349. [Google Scholar]

- Sláma, K.; Koudela, K.; Tenora, J.; Maťhová, A. Insect hormones in vertebrates: Anabolic effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone in Japanese quail. Experientia 1996, 52, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Tang, N.; Liu, F.; Huang, G.; Jiang, X.; Gui, G.; Wang, L.; et al. Effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone on improving memory deficits in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus in rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roumanille, R.; Vernus, B.; Brioche, T.; Descossy, V.; Van Ba, C.T.; Campredon, S.; Philippe, A.G.; Delobel, P.; Bertrand-Gaday, C.; Chopard, A.; et al. Acute and chronic effects of Rhaponticum carthamoides and Rhodiola rosea extracts supplementation coupled to resistance exercise on muscle protein synthesis and mechanical power in rats. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2020, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.P.; Gerbarg, P.L.; Ramazanov, Z. Rhodiola rosea: A phytomedicinal overview. Herbal. Gram. 2002, 56, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, W.-L.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Bai, R.-Y.; Sun, L.-K.; Li, W.-H.; Yu, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, Z.-X.; Peng, Y.-F.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Rhodiola rosea L.: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanum, F.; Bawa, A.S.; Singh, B. Rhodiola rosea: A versatile adaptogen. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2005, 4, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A.; Seo, E.-J.; Efferth, T. Novel molecular mechanisms for the adaptogenic effects of herbal extracts on isolated brain cells using systems biology. Phytomedicine 2018, 50, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballmann, C.G.; Maze, S.B.; Wells, A.C.; Marshall, M.R.; Rogers, R.R. Effects of short-term Rhodiola Rosea (golden root extract) supplementation on anaerobic exercise performance. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jówko, E.; Sadowski, J.; Długołęcka, B.; Gierczuk, D.; Opaszowski, B.; Cieśliński, I. Effects of Rhodiola rosea supplementation on mental performance, physical capacity, and oxidative stress biomarkers in healthy men. J. Sport Health Sci. 2018, 7, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abidov, M.; Grachev, S.; Seifulla, R.D.; Ziegenfuss, T.N. Extract of Rhodiola rosea radix reduces the level of c-reactive protein and creatinine kinase in the blood. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2004, 138, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Heufelder, A.; Zimmermann, A. Therapeutic effects and safety of Rhodiola rosea extract WS® 1375 in subjects with life-stress symptoms—Results of an open-label study. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov, V.; Zholus, B.; Shervarly, V.; Vol’Skij, V.; Korovin, Y.; Khristich, M.; Roslyakova, N.; Wikman, G. A randomized trial of two different doses of a SHR-5 Rhodiola rosea extract versus placebo and control of capacity for mental work. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darbinyan, V.; Aslanyan, G.; Amroyan, E.; Gabrielyan, E.; Malmström, C.; Panossian, A. Clinical trial of Rhodiola rosea L. extract SHR-5 in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanely, R.A.; Nieman, D.C.; Zwetsloot, K.A.; Knab, A.M.; Imagita, H.; Luo, B.; Davis, B.; Zubeldia, J.M. Evaluation of Rhodiola rosea supplementation on skeletal muscle damage and inflammation in runners following a competitive marathon. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 39, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stejnborn, A.S.; Pilaczyńska-Szcześniak, S.; Basta, P.; Deskur-Śmielecka, E. The influence of supplementation with Rhodiola rosea L. Extract on selected redox parameters in professional rowers. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2009, 19, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parisi, A.; Tranchita, E.; Duranti, G.; Ciminelli, E.; Quaranta, F.; Ceci, R.; Sabatini, S. Effects of chronic Rhodiola Rosea sup-plementation on sport performance and antioxidant capacity in trained male: Preliminary results. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2010, 50, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Bystritsky, A.; Kerwin, L.; Feusner, J.D. A pilot study of Rhodiola rosea (Rhodax®) for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2008, 14, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hancke, J.; Burgos, R.; Ahumada, F. Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, D.-F. Analysis of Schisandra chinensis and Schisandra sphenanthera. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 1980–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A.; Wikman, G. Pharmacology of Schisandra chinensis bail.: An overview of Russian research and uses in medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, J.; Táborská, E.; Lojková, L. Lignans in the seeds and fruits of Schisandra chinensis cultured in Europe. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care. Schisandrae chinensis fructus. In European Pharmacopoeia, Monograph 07/2016:2428; Corrected 9.1, Corrected 7.0; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care: Strasburg, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szopa, A.; Barnaś, M.; Ekiert, H. Phytochemical studies and biological activity of three Chinese Schisandra species (Schisandra sphenanthera, Schisandra henryi and Schisandra rubriflora): Current findings and future applications. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kochetkov, N.; Khorlin, A.; Chizhov, O.; Sheichenko, V. Schizandrin—Lignan of unusual structure. Tetrahedron Lett. 1961, 2, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.-F.; Zhang, S.-X.; Kozuka, M.; Sun, Q.-Z.; Feng, J.; Wang, Q.; Mukainaka, T.; Nobukuni, Y.; Tokuda, H.; Nishino, H.; et al. Interiotherins C and D, two new lignans from Kadsurainteriorand antitumor-promoting effects of related neolignans on Epstein−Barr Virus Activation. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.H.; Lee, M.; Lee, M.W.; Lim, S.Y.; Shin, J.; Kim, D.-H. Effects of Schisandra lignans on P-Glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux in human intestinal Caco-2 Cells. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, W.-F.; Wan, C.-K.; Zhu, G.-Y.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Dey, S.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, X.-L. Schisandrol A from Schisandra chinensis reverses P-Glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by affecting Pgp-substrate complexes. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, M.; Kilgore, N.; Lee, K.-H.; Chen, D.-F. Rubrisandrins A and B, lignans and related anti-HIV compounds from Schisandra rubriflora. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.-F.; Zhang, S.-X.; Xie, L.; Xie, J.-X.; Chen, K.; Kashiwada, Y.; Zhou, B.-N.; Wang, P.; Cosentino, L.; Lee, K.-H. Anti-aids agents—XXVI. Structure-activity correlations of Gomisin-G-related anti-HIV lignans from Kadsura interior and of related synthetic analogues. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 1997, 5, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Q.; Li, D. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oil from berries of Schisandra chinensis(Turcz.) Baill. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 2199–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zu, Y.; Yang, L. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oil of Schisandra chinensisfruits. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yan, T.; Gong, G.; Wu, B.; He, B.; Du, Y.; Xiao, F.; Jia, Y. Purification, structural characterization, and cognitive improvement activity of a polysaccharides from Schisandra chinensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, J.-T.; Wang, Z.-B.; Li, Z.-Y.; Zheng, G.-X.; Xia, Y.-G.; Yang, B.-Y.; Kuang, H.-X. Aromatic monoterpenoid glycosides from rattan stems of Schisandra chinensis and their neuroprotective activities. Fitoterapia 2019, 134, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocan, A.; Crișan, G.; Vlase, L.; Crișan, O.; Vodnar, D.C.; Raita, O.; Gheldiu, A.-M.; Toiu, A.; Oprean, R.; Tilea, I. Comparative studies on polyphenolic composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of schisandra chinensis leaves and fruits. Molecules 2014, 19, 15162–15179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, B.-Y.; Guo, J.-T.; Li, Z.-Y.; Wang, C.-F.; Wang, Z.-B.; Wang, Q.-H.; Kuang, H.-X. New Thymoquinol Glycosides and Neuroprotective Dibenzocyclooctane Lignans from the Rattan Stems ofSchisandra chinensis. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Han, S.; Park, H. Effect of Schisandra chinensis extract supplementation on quadriceps muscle strength and fatigue in adult women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, J.Y.; Kim, K.H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Schisandra chinensis for menopausal symptoms. Climacteric 2016, 19, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.-Y.; Wang, J.; Eom, T.; Kim, H. Schisandra chinensis fruit modulates the gut microbiota composition in association with metabolic markers in obese women: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Shang, H.; Wu, W.; Du, J.; Putheti, R. Evaluation of anti-athletic fatigue activity of Schizandra chinensis aqueous extracts in mice. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 3, 593–597. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Shao, J.-Q.; Du, H.; Wang, Y.-T.; Peng, L. Effect of Schisandra chinensis on interleukins, glucose metabolism, and pituitary-adrenal and gonadal axis in rats under strenuous swimming exercise. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2014, 21, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cao, J.; Sun, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Ethanol extract of Schisandrae chinensis fructus ameliorates the extent of experimentally induced atherosclerosis in rats by increasing antioxidant capacity and improving endothelial dysfunction. Pharm. Biol. 2018, 56, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.-H.; Liu, X.; Cong, L.-X.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Chen, J.-G.; Wang, C.-M. Metabolomics study of the therapeutic mechanism of Schisandra chinensis lignans in diet-induced hyperlipidemia mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ip, S.-P.; Poon, M.; Wu, S.; Che, C.; Ng, K.; Kong, Y.; Ko, K. Effect of Schisandrin B on hepatic glutathione antioxidant system in mice: Protection against carbon tetrachloride toxicity. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridharan, V.V.; Thandavarayan, R.A.; Sato, S.; Ko, K.M.; Konishi, T. Prevention of scopolamine-induced memory deficits by schisandrin B, an antioxidant lignan from Schisandra chinensis in mice. Free. Radic. Res. 2011, 45, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-Y.; Ku, S.-K.; Lee, K.-W.; Song, C.-H.; An, W.G. Muscle-protective effects of Schisandrae fructus extracts in old mice after chronic forced exercise. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 212, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, F.; Liang, S. An immunostimulatory polysaccharide (SCP-IIa) from the fruit of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 50, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Mao, G.-H.; Zhang, M.; Li, F.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, D.-H.; Yang, L.-Q.; Wu, X.-Y. Anti-diabetic effects of polysaccharides from ethanol-insoluble residue of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) baill on alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2012, 29, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).